Take it offline!

This Education in Motion resource is also available as a printable PDF.

Download PDF

There are many differences in the musculature of children with cerebral palsy (CP) compared to musculature of typically developing children. Here are six key differences which will influence, and can be influenced by, therapy.

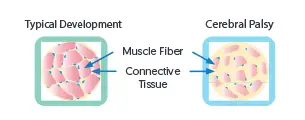

Increased amount of connective tissue

Changes in the DNA lead to a greater proportion of connective tissue compared to muscle fibers in the muscle fiber bundles. This increased proportion of connective tissue leads to increased stiffness of the muscle.

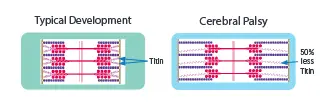

Reduced sarcomere stiffness

Myofibrils (lengths of sarcomeres in series) have 50% less Titin (a large protein essential for sarcomere structure and muscle tone), and therefore are less stiff. This loss of Titin may be a secondary adaptive response which partially offsets the high passive stiffness from the increased connective tissue.

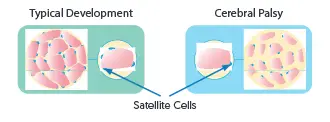

Reduced number of satellite cells

There is a significantly lower number of satellite cells (the stem cells that generate new sarcomeres). This reduction in satellite cells may contribute to reduced capacity for growth and repair and could influence the likelihood of contractures.

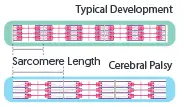

Increased sarcomere length, but reduction in number

A reduced number of satellite cells likely contributes to a reduced capacity for new sarcomere production, leading to decreased range of movement with bone growth. The sarcomeres that are present are longer in length, and when in their longest position will produce less force, potentially influencing the formation of contractures.

Reduced muscle volume / cross-sectional area

There is reduced muscle volume due to a lower number of fibers and/or a decrease in the average fiber cross-sectional area. This may lead to muscle weakness. Muscle growth is the same in early infancy and then decreases at 12-15 months of age. This may be related to reduced physical activity and lower neural activation caused by less opportunities for activity.

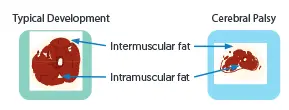

Increased intermuscular and intramuscular adipose tissue

There is an increased proportion of intermuscular and intramuscular fat. Lower levels of physical activity are thought to be a contributor to this.

References

- Lieber, R. L., & Fridén, J. (2019). Muscle contracture and passive mechanics in cerebral palsy. Journal of applied physiology.

- Howard JJ and Herzog W (2021) Skeletal Muscle in Cerebral Palsy: From Belly to Myofibril. Front. Neurol. 12:620852. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2021.620852

- Lieber, R. L., & Theologis, T. (2021). Muscle-tendon unit in children with cerebral palsy. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 63(8), 908-913.

- Dayanidhi, S., Dykstra, P. B., Lyubasyuk, V., McKay, B. R., Chambers, H. G., & Lieber, R. L. (2015). Reduced satellite cell number in situ in muscular contractures from children with cerebral palsy. Journal of Orthopaedic Research, 33(7), 1039-1045.

- Mathewson, M. A., & Lieber, R. L. (2015). Pathophysiology of muscle contractures in cerebral palsy. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Clinics, 26(1), 57-67.